Preserving Family History: An Act of Resistance (Learning Resource)

- Apr 8, 2020

- 13 min read

Updated: Apr 9, 2020

In this post, I share an interdisciplinary learning project that I developed for my classes during lockdown. This unit will help young people develop closer bonds with their relatives, strengthen their sense of identity and gain a better understanding of the past as well as the present. This project is appropriate for pupils of any racial identity; for pupils of colour it becomes a powerful act of resistance.

Gathering family stories that would otherwise be lost, erased and denied allows us to learn about our elders' lives under colonial rules. It is a crucial aspect of decolonising the curriculum, especially the typically white-washed History taught in schools.

The unit I developed for my own National 5 and Higher English classes could be adapted for pupils in S1 - S6 (11 - 17 years old).

For older pupils, this unit would be a good starting point for a reflective or creative essay for the National 5 or Higher portfolio. The unit presents other possible outcomes for younger pupils (even in primary school), such as designing the missing pages of a History textbook, creating a newspaper article, writing a poem, drawing a comic and making a Thank You postcard inspired by family stories. In fact, you could use this project as a parent with your children or as an individual looking for some structure to guide the discovery of your own family history. If you would like to get a free PDF version of my unit, please send your request to theantiracisteducator@gmail.com

Preserving Family History Project

Once Upon a Lockdown…

A lot of us will be stuck at home with our family, spending a lot more time with our relatives (whether we like it or not).

This is the perfect chance to bond and learn more about our family’s past.

We think we know our family members and their lives, but now we can discover some of the stories that we’ve never heard before.

A Phone Call Away…

For some of us, our family may be far, far away. But technology is great for helping us stay in touch.

Now is the time to Skype, FaceTime, Zoom or make a simple phone call to speak to the relatives who do not currently live with you.

For this project, you will need:

- A pen and some paper to take notes

- A device to make calls (if you want to speak to family members not currently living with you)

- Relatives to speak to (arrange this in advance if they are busy)

- Curiosity, compassion and creativity

- An open mind

At the end of this project, you will have recorded some of your family stories to preserve and celebrate your family’s history. This could be through a piece of writing and a piece of art.

What counts as History?

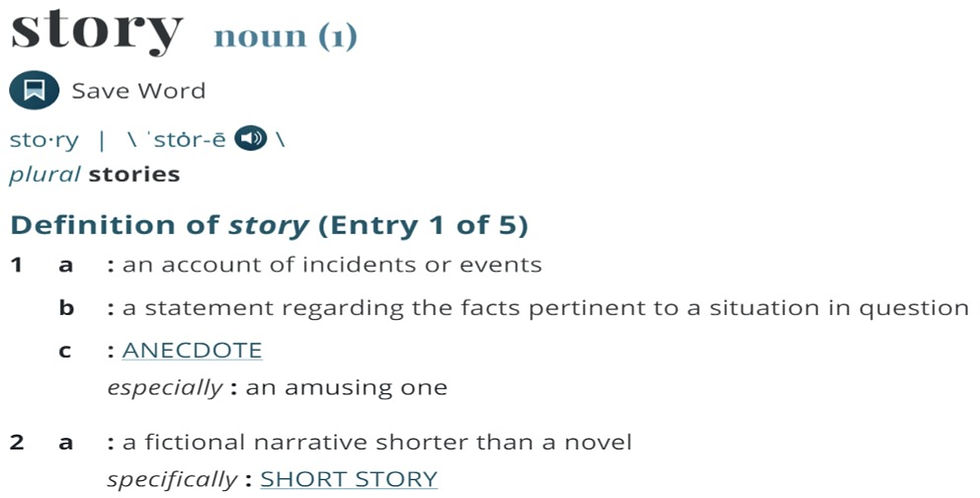

We often think that ‘history’ refers to all the big, significant world events. However, the definitions of ‘history’ may vary. Take a look at the following definitions and consider which ones resonate the most with your understanding.

The second pictured definition focuses on the idea of a ‘story.’ In that sense, the history of your family will be made of all the stories family members have to tell.

Bear in mind that there are many sides to one story.

Those different family perspectives can make our history all the more exciting. Our family may very well have a different side to the stories present in History textbooks.

Where Is My History?

British-Pakistani poet, Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan explores what ‘history’ means to her in her poem entitled "Where Is My History?" She pays particular attention to her family’s history that tends to be forgotten in all the History textbooks and museums.

Here is an extract from her poem for you to think about:

My history is imprinted in the spaces between the ink printed on pressed pages

My history is the screams shouting out through the silent slots in syllabi

It is caged in glass cases said to be for its own safety by the institutions which narrate it as their own

Because my history lies in the choices not recorded

About which stories should be hoarded

And called archives

And my archives

Are the chicken shops

The taxi stops

The backseats of rentals

And inside hems of headscarves

Women’s conversations

Women’s congregations

Women’s contemplations

Which you won’t find in your local heritage siteWhen we study history, we tend to focus on ‘significant’ events in a country and around the world. However, who gets to decide what counts as ‘significant’?

Who decides whose stories are more important?

Churchill himself is guilty of being a "victor writing History": he claimed that the Bengal famine was caused by Indians "breeding like rabbits" rather than admitting that his own colonial policies were responsible for the famine.

Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan's poem highlights the fact that a lot of our family history is not recorded and not included in textbooks and museums. By investigating and recording some of your family history, you will get a chance to take back control. You will get to preserve and celebrate the stories of your relatives and ancestors that may otherwise be forgotten.

Family Tree

Use the family tree below to get you started, starting off with yourself at the bottom, your parents above that, their parents and so on. Use the space around and above the tree to add extra boxes and branches as required (aunts, uncles, step-mothers/fathers, etc.). Alternatively, you can use an online family tree creator following this link.

How far out do your branches reach out? Can you extend any branches and add more boxes? Are there people missing that you don’t know about? You can ask a family member to help you at this stage.

Jot down the things you already know about your family members on the tree. If you run out of space, you can do this on a separate sheet of paper. This could include:

names/nicknames (and the stories behind these)

relationships

jobs

significant family events (weddings, birthdays, funerals, etc.)

world/national events that may have affected your family (wars, national independence, civil rights/women’s rights movements, genocides, persecutions, famines, plagues, natural disasters, etc.)

Preparing Questions

The Interviewer (you)

Are there any gaps on your tree? Are there things you simply don’t know? Write down any questions that have come to your mind about your family’s experiences:

Questions:

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What stories have you already heard from your relatives? What else could you find out about those stories? Or are there any new stories you would like to hear?

Take notes of those stories as follows:

1. Stories I know

E.g. That time when my parents first met.

2. Questions about those stories

E.g. What were their first impressions of each other? When did they first realise that they were ready to get married?

3. New stories I would like to discover

E.g.The first time grandmother was allowed to vote.

These are some of the family stories and questions my class came up with during our first week of lockdown and virtual learning:

What was it like being a wartime type-writer?

How did you fight off a snake in the village?

Whose idea was it to put me (as a baby) in the fridge when it was too hot? And what were they thinking?

What was your scariest experience as a police officer?

Why did you run away from boarding school?

What was it like for my great-grandfather to fight for the British during World War One? He was stuck in Burma and he had to walk all the way back home to India using leaves as shoes.

What was it like moving away from Pakistan to build a family in the UK? Do you regret your choice?

What was it like living in Glasgow tenements with temporary shelters for air raids during World War Two?

What was it like for my grandmother to experience the loss of her daughter who suffered from malnutrition?

How did it feel for my grandfather to leave his remote village in Pakistan, get a degree and move to the UK, against all the odds?

What was it like being forced to leave Iraq because of war?

How did grandmother feel when she married grandfather and had to live with his other wives?

What was it like to go to the cinema for the first time?

How did grandfather escape after being captured as a prisoner of war?

What was your favourite thing about opening a restaurant?

Other generic questions:

· What does "home" mean to you?

· Tell me about your earliest memory?

· What are you most proud of in your life?

· What are some of the scariest moments of your life?

· What are some of the happiest moments of your life?

· What are some of the saddest moments of your life?

· What are some of the most difficult times of your life?

· Tell me about some of the most exciting experiences in your life.

· Do you have any claims to fame?

· Do you have any regrets?

· If you could go back in time and relive one moment in your life, what would it be? Why? Tell me more about it.

· Who were your role models in life? What did you admire about them?

· Could you share what you have learned about life? What wisdom could you share with me?

Take a note of other questions you would like to ask.

__________________________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Interviewee(s) (family members)

Once you have thought of questions, you might want to think of the best people to ask for this project. Unfortunately, not all our relatives will be alive to answer the questions we might have for them. However, you might find that those who are alive may have their answers for you!

You may choose several people to speak to and you might even gather different versions of the same story. The more perspectives, the better!

· Interviewee 1: ______________________________

How will I speak to them (circle the answer): in person / phone call

When would be a good time for them? ________________________

Will I need anybody to help me speak to them (if they speak a different language for example, or if they struggle with disabilities)? ___________

· Interviewee 2: ______________________________

How will I speak to them (circle the answer): in person / phone call

When would be a good time for them? ________________________

Will I need anybody to help me speak to them (if they speak a different language for example, or if they struggle with disabilities)? ___________

· Interviewee 3: ______________________________

How will I speak to them (circle the answer): in person / phone call

When would be a good time for them? ________________________

Will I need anybody to help me speak to them (if they speak a different language for example, or if they struggle with disabilities)? __________

The Interviewing Process

Make sure that your interviewees are aware that this is a school project and that you will be recording and using some of their stories. There are many ways of recording stories this:

- Write notes on paper

- Type notes in a Word document on a tablet or Ipad

- Use a phone to record what your relative is saying

- Doodle some ideas while you listen to their stories

Active listening means asking questions…

It doesn’t have to be a one-way conversation.

Ask questions to check that you understand everything they are telling you.

Show that you are listening by nodding, smiling and using your body language to show that you care.

However, you don’t want to be firing away questions one after the other. That can put people off… We all need time to think when we are asked questions. And it takes time to tell stories properly, from beginning to end. Give your interviewee time to think and develop their answers and stories. Be patient and enjoy the conversation.

You don’t have to stick to a script. Express your reactions, your surprise, your compassion and your curiosity when hearing new stories.

Take a note of your feelings because this might help you with your final piece of writing/art.

Hearing these family stories made me feel…

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

You may have more questions after the conversation is over. Take a note of these and, later on, pick up the conversation where you left it. Repeat the interviewing process several times to get the juiciest bits of your family stories!

Transforming Oral Stories

Using your notes, pick your favourite bits of the family history you explored. Use these ideas to create any of the following genres of writing:

- A reflective essay

- A creative short story

- A poem

- A comic

- A newspaper article

- The missing pages of a History textbook

- A postcard

You can test a couple of them first and you can choose to do more than one (e.g. a poem and a postcard). The next part of this unit provides guidance for each genre.

A Reflective Essay

For this type of writing, you will need to write the story from your personal perspective. Reflection involves contemplating, thinking more deeply about what you learned from this process of hearing family stories.

Using some of these questions may guide your reflection:

Did you have any interesting realisations about your family?

How did it feel discovering this family history?

Did it change your impression of your family?

How did it affect your sense of identity?

Has your understanding of your family heritage changed?

Do you think you used to value your family members enough before this process?

A reflective essay can take the form of:

a short story (with a beginning, middle and end)

a motivational speech

a letter to your future/past self or a family member

a diary entry

Here is an extract from a reflective essay written by an S4 pupil. He reflects on his mother’s incredible story from her childhood when she lived in a remote village in India.

For a split second the eyes of the wolf and my mum lock together. Her eyes sunk with fear and she let out a deafening shriek that woke the entire village from their slumber. (…) She ran as fast as her legs could carry but the wolf was too quick, which was slowly closing the distance between them. Her determination to live was remarkable, knowing fine well the slim odds of her survival, yet she still persevered. (…) It’s unsettling to think about how quickly things can change. My mum was jolted from her tranquil sleep and soon running for her life, filled with shock and horror. But the wolf on the other hand, it could taste victory, but soon lost everything, including its life.A Creative Essay

For this type of writing, you can ‘embellish’ your family history and use your imagination to fill in the gaps.

For example, my mother recently told me that one of her distant aunts in India was a black woman who looked like she had African ancestry. My mother doesn’t know anything beyond that potential history, but I could fill in the gaps based on my understanding of Indian history, colonisation and the slave trade. It is very likely that my ancestors were a mix of African slaves transported to Goa, Portuguese colonisers and native Indians. Now, I can use my imagination to fill in the gap and describe what my ancestors’ lives may have been like.You probably only heard one side of the story, so you could play around with different perspectives to figure out what would bring the story to life. Toni Morrison does the same in her award-winning novel, Beloved. The following extract explains what inspired her to write the story:

Margaret Garner, a young mother who, having escaped slavery, was arrested for killing her children (and trying to kill the others) rather than let them be returned to the owner’s plantation. (…)

The historical Margaret Garner is fascinating, but to a novelist, confining. (…) So I would invent her thoughts, plumb them for a subtext that was historically true in essence, but not strictly factual in order to relate her history to contemporary issues about freedom, responsibility and women’s “place.” The heroine would represent the unapologetic acceptance of shame and terror; assume the consequences of choosing infanticide; claim her own freedom. The terrain, slavery, was formidable and pathless. To invite readers (and myself) into the repellent landscape (hidden, but not completely; deliberately buried, but not forgotten) was to pitch a tent in a cemetery inhabited by highly vocal ghosts.A Poem

Poetry requires you to be brief and concise. It often requires a process of writing and re-writing:

Try writing a few paragraphs about your chosen story or experience, emphasising emotions and using as much description as possible.

Underline the key words and emotions that stand out

Create a word bank to see if you can come up with synonyms and better ways of expressing the key words you underlined.

Play around with the structure of your poem to create a rhythm (saying it out loud will help).

In the following poem, Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan celebrates her grandmother’s everyday life.

Nani

She smells like untouched snow

And morning mountain dew

Her fingers peel potato skins

Like unwrapping giggles from children’s lips

She coaxes rice grains into scoops

And evaluates inexact measurements exactly

(…)

She slips money into children’s hands with a two-eyed wink

And she is fresh fresh freshly bathed

Clean like rose water

Knees like old age

But lips murmur over English words

Learning learning learning

She gave and she givesNairobi Thompson’s collection of poems (Bayonets, Mangoes and Beads: African Diasporic Voices from WWI and WWII) explores the forgotten history of the African diaspora’s contributions to World Wars. The following poem conveys the experience of Senegalese soldiers forced to join the French army, drawing strong parallels to slavery (which was officially abolished at the time).

Dark Forces

Villages were raided to fill French quotas

For French trenches

Hard task masters sent

Bent on capture of the poorest from Senegal

Ripping them from soft loving arms of wailing mothers

Old fathers, new wives, new borns

Leaving broken families of unplanted fields

So too defenceless orphan boys – stolen children

With no one to fight for them were taken

Bound in chains and herded to the collection stations. Herded and bound. Herded and bound in chains. Not slaves. Not this time. Called to save. Not slaves. Shipped to Europe in the belly of the ship. In the ship’s hungry belly. Not slaves. Not slaves. Not this time.

(…)

The Force Noire. Forced to enlist. To be a tour de force to be reckoned with. Conscripted to fight for Liberté, égalité, fraternité. Emancipation – for everyone as long as it was not their own.A Comic

A lot like poetry, comics require you to be brief and selective with your use of words. Images should enhance the plot, allowing you to show the story rather than tell. Also a lot like a short story, you need to make sure there is a clear beginning, middle and end.

The extracts above come from the graphic novel ‘Freedom Bound: Escaping Slavery in Scoltand’ by Warren Pleece, Shazleen Khan and Robin Jones. Just like the creative short story, you may need to use your imagination to fill in the gaps. However, it is also possible to be more factual and reflective if you wish to stick more closely to your interviewee’s stories.

Newspaper Article or Missing Pages from a History Textbook

In the following extract, Suhaiymah Manzoor-Khan questions what counts as ‘significant’ enough to be classed as History.

On one level, ‘where’ my past is is a question of where it is in what is called the subject of History. My past is missing from textbooks, curriculums and documentary and other recordings of History in the sense that if the history of, for example, Pakistan is told, it is told through the eyes of diplomats, South Asian elites and Britons with their own assumptions and political goals.

Or in the case of migration, the history of Pakistani migrants to the UK is told as part of the history of ‘migration’ which obscures the role of British colonialism and the commonwealth in that migration. It also often obscures the place of women – who are not only excluded from ‘migrant’ histories but also ‘women’s history’ (for being migrants) and larger ‘British history.’

Such placement of my history is an outcome of the decisions that go into selecting what is a historical document and what is not – e.g. what piece of evidence is an important piece of the past and what piece of evidence is not: what is a scribble on a piece of paper and what is a ‘source,’ what is an oral history and what is a story told by my grandma? By selecting the most interesting and exciting parts of your interviewees’ stories, you have the choice of:

Writing a newspaper article with the story as a headline (as if it was published at the time that it happened).

Writing a page from a textbook that uses your family’s stories as source to inform the reader about some aspect of your (or the world’s) history.

You can look up examples of contemporary newspaper front pages or History textbooks to follow as a model.

A Postcard

This is a great way to thank your interviewees for taking part. You could illustrate one of their stories and write and thank you message for them.

Possible illustrations for the front:

An extract from your comic

Your favourite lines from your creative writing/reflective essay

Your poem with illustrations

Your newspaper headlines

A picture of their favourite moment/story in life

What you could write at the back:

Thank them for taking part in your school project

Express your gratitude for their time and patience during the interview

Explain how it made you feel to hear their stories

Tell them how much you love them

If you enjoyed this project and completed any of the written and artistic outcomes, please share them with us by sending us an email (theantiracisteducator@gmail.com) or tagging us on Twitter (@AntiRacistEd). We'd love to discover your decolonised versions of history!

Best amazing blog i like it The Repelis24

The largest call girls’ ads selection in Surat. Browse in our call girl category for finding a MEETING FOR SEX in Surat.

Escorts in Surat Escorts in Pune Escorts in Chennai Escorts in agra Escorts in ghaziabad Escorts in navsari Escorts in nadiad

Thanks for the nice blog. It was very useful for me. I’m happy I found this blog. Thank you for sharing with us,I too always learn something new from your post. You may discover more about call girls in Visakhapatnam if you're interested.

Nice post. Men who are looking for ways to recharge romantic fire. First of all, join my contact agent to get my work details. You and Heena will be one during the weekend. For an outstation, you need to book this independent escorts in Visakhapatnam in advance.

This sounds like a wonderful project! Connecting with family history is so important. It reminds me of how fans piece together the lore in Fnaf, uncovering secrets and understanding the story's deeper layers. This project helps students do something similar, piecing together their own past. What a fantastic way to foster identity and understanding, especially in these times. I imagine it could spark some truly fascinating discussions.